|

August 14, 2020

Weaving and making fabrics sound like some sort of subject out of a soporific portfolio, but actually, it's worthwhile to study and know about the properties and what weaving can and cannot do. Such terms as bias, on the grain, against the grain, provide just a few insider information that can help us not only make better selections in our fabric but also how better to assemble our fabric. This can also improve our hand in the feel of a fabric. A fabric always

has a "hand," and an expert hand can tell us a lot. You may think you don't have an expert or even knowledgeable hand, but you probably know more than you think you do.

This isn't so much about fiber content, like silk, rayon, or wool. This is about how the fabric is put together. So let's start with the yarn. So the yarn is procured, through growing (plants like flax and cotton and linen), through animal harvesting (through shearing animals or silkworm cocoon) or man-made. Most natural fibers take more processing and have more steps before they are actually made into a yarn. The man-made fibers have already undergone

processing to produce the yarn, so need little if any processing.

The natural fibers are sorted and graded.

Wool is graded from virgin wool and regular wool. Virgin wool is the first cut from a lamb and sometimes includes the wool sheared from the stomach and other hidden areas. The "first cut" means that the wool tips which have never been cut are smoother and softer than the regular cut from an animal that has been sheared before. If you touch wool, and it's soft and lustrous, it is most likely virgin

wool.

Cotton is carded, which cleans the bales to remove the trash from the wanted fiber. The fibers are combed and graded and packed into bales. From here, cotton undergoes more processing. Most cotton is mercerized, a process by which the fiber is changed to accept dye better and become more lustrous. Mercerization is a process that pretty much saved the cotton fiber industry and makes cotton one of the most prolific and most common fiber in the world today.

Linen harvested from the plants undergoes much more processing to make the linen we all know. Linen and flax can be very scratching and stiff, and processing the fiber makes it more useful. In the case of handkerchief linen and light-weight linens, they can be so smooth and comfortable because of this processing.

The silk cocoon is unwound and is a long, very smooth, and, therefore, lustrous fiber. Silk is a fiber that requires very little processing. Basically, it's washed and the clutter or trash removed, and that's it. Because of its rarity and beauty, it is considered the most luxurious and expensive of fabrics.

So out of these different fabrics, obviously you can tell that if the fiber in the thread or yarn is shorter, it's going to make a scratchier and less shiny fabric.

Spinning

Now that the fibers have been prepared for use, they need to be spun. This is a matter of twisting the yarn so that it will become a thread. Like all processes in making fabric, the more yarns used, the stronger and better the fabric. That even applies to textiles such as gauze, organza, chiffon, and other feather-weight textiles. It especially applies to these fabrics, because the fabric weave is so delicate that if

the yarn doesn't have any substance, then the textile can be flimsy and can hardly withstand the process of sewing, much less wearing for any length of time.

When you touch a fabric that looks substantial but is thin, and there doesn't seem much to it, it's because it has fewer fibers in the yard that it is woven with. This is one of the results of the fast/cheap fashion industry that constantly sought to deliver a product at a cheaper and cheaper price for each production run. As a result, fabrics that were woven with threads that had 10 or more yarns per thread, were woven with 2 or 3 yarns per thread. You can only

imagine how thin and flimsy this fabric was. This was added to less yarns per inch so the fabric was not only woven with a far thinner thread but with fewer threads per inch.

Don't be dismayed if you think you can't tell the difference by touching these kinds of fabric to determine if they are really inexpensive or poorly made. You can. Why? Because above any other prospective consumers out there, we sewists are more familiar with fabric that we think.

The weave

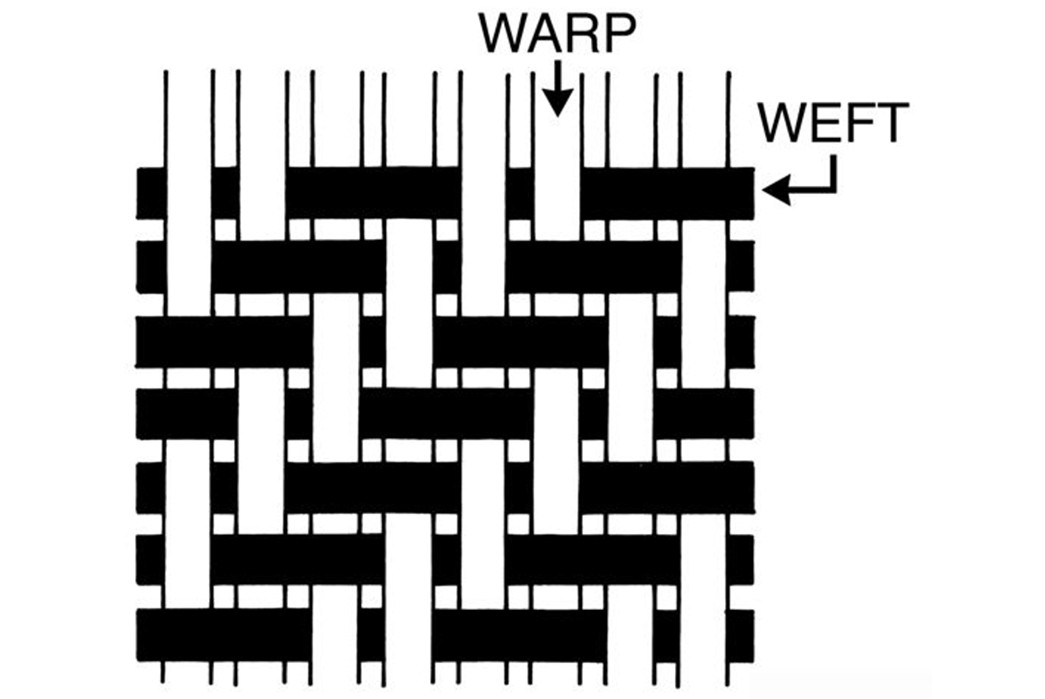

Now that we have the threads (or yarns), we need to weave them into fabric. You can lots of different weaves, like plain weave, basketweave, jacquards, satin, twill and lino. Jacquards include brocades, tapestries, and damask. This is how the fabric is put into the loom and treated. The plain weave is a simple an in and out with the next row alternating the "out" from the former row as an "in" on

the following row. The best way to describe these weaves is to show what they are.

This is the plain weave, in and out both within the row and from row to row.

Instead of each row and warp thread alternating, this is every two threads being alternated. This simply makes a more pronounced basketweave look.

Another common weave is a twill which you see in jacket, pants and suits. This makes a very sturdy and stable weave and is usally done with much heftier threads. Although this is also the common weave for silk ties and scarves.

Jacquards like brocade, damask and tapestries are woven with a particular design in mind. The design can be woven so that the weave is alternated to display a design or can be different colored threads woven into make the design.

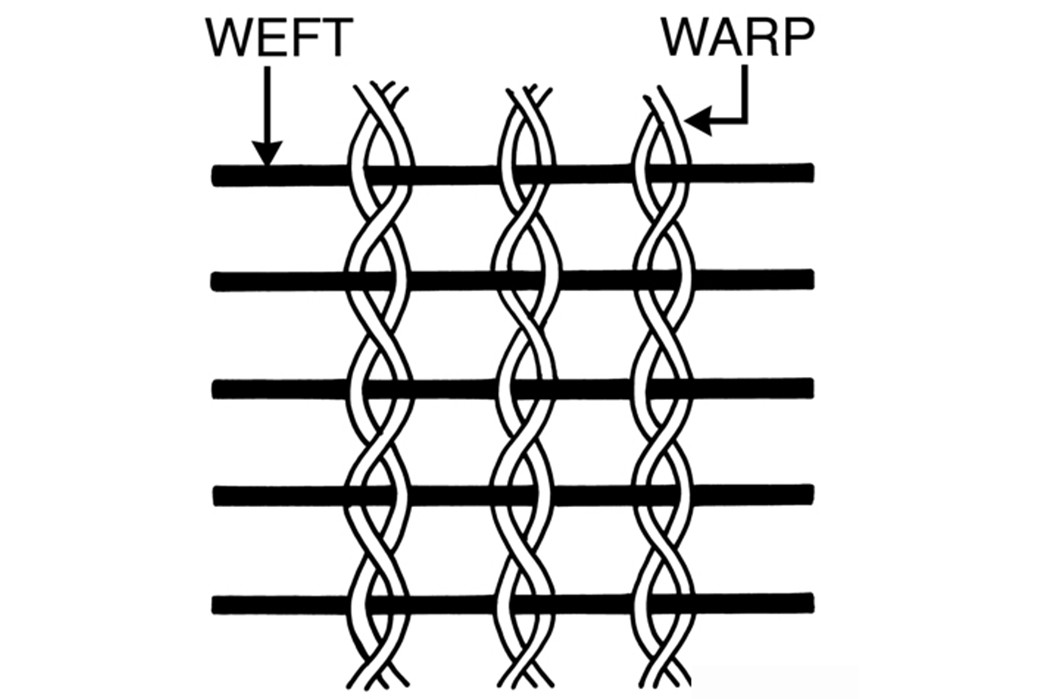

Lino includes gauzes, and other light weight loosely woven fabrics which are woven with a twist in the yarn. This acts as a stable weave in these delicate fabrics. It makes them able to withstand assembly processes as well as lasting after they are assembled! Lino includes gauzes, and other light weight loosely woven fabrics which are woven with a twist in the yarn. This acts as a stable weave in these delicate fabrics. It makes them able to withstand assembly processes as well as lasting after they are assembled!

The Weaving Process

So fabrics are woven on a loom, duh! But picturing the loom helps to understand some important principles about woven fabrics.

Now imagine cutting on the warp grain. This is the widthwise grain that the shuttle carries in and out through the fabric. If this thread breaks, then you can simply tie a knot onto another thread and keep going. At the same time, this is not the stronger of the grains, and cutting on this grain can cause a garment to shift and hang unevenly over time.

These are some of the thing that are handy to know because you know how the fabric is woven.

Another secret that's handy to know is that when you are sewing, you always start at the large end, and sew toward the small end. You sew from large to small. The reason you do this is to avoid the rippling effect, and believe me it works - try it on a piece of muslin and you will be shocked. The reason is that you are working with the straight grain of the fabric to help keep the fabric as stable as possible even though you're a little off the grain and a little

more on the bias. Of course these seem always need pressing, and don't ever prejudge your seem till you press it.

So let's say you have a fabric and you'd like a part of it to stretch or at the least, have a little bit of ease to it. But all you have is the woven fabric and you want everything in the garment to match. What do you do? You use the bias, which is the least stable and has a little stretch to it. This bias is also fabulous for draping and folding like a cowl neck. Cutting a cowl neck from a bias piece and a straight piece will make you a devotee of the

bias cut!

This is also why you let a skirt that is cut a little or a lot on the bias hang for 24 hours before you hem it. This allows the bias and more specifically the loosely woven warp weave to "hang" so that your hem won't be as wobbly otherwise.

As a lark - here's a very cool video of a very fast loom

This is so fast, that it's virtually impossible to see the shuttle but it's there, cause you can see the design being woven in the fabric. The reed (or I like to call the cramer cause it crams the woof weave down close to the former woof weave), is hard to see as well. This is the Toyota Jet Loom running at 800 RPM (repetitions per minute). You can see the shafts working to create the design in the fabric, but it's hard to think about something this fast, but

this is how fabric is made today.

The last important thing to remember here is that weaving is different from content. Weaving is the satin, brocade, lino type description while the content is what the yarn or thread is made of - a blend of poly and natural, or all wool, or wool & cotton - that sort of description.

Stretch Fabrics

Not to forget stretch fabrics here. There are two types of stretch fabrics - content and woven.

Content Stretch Fabrics

So content stretch fabrics have a content of Lycra, Elastane, or Spandex. These are all the same thing, but different trade names. So when you see a fabric that has 97% cotton and 3% Lycra, it will stretch. Sometimes you'll see 95% straight fabric and 5% Lycra. Content stretch fabrics occur in both percentages. They do stretch, but the stretch is very minimal. Usually the stretch on these fabrics vary between 5% to at most 15%. In the stretch

world, that's not very much stretch. That's why I use only woven patterns for these content stretch fabrics.

Woven Stretch Fabrics

These are often knitted fabrics. This means that it is woven with a stretch in mind. The stretch percentage on these can vary from 20% (a stable ponte or double knit) to a 50% (a jersey) to 200% and up (activewear). Some activewear can stretch 2 to 3 times it's original relaxed state. These are often knitted fabrics. This means that it is woven with a stretch in mind. The stretch percentage on these can vary from 20% (a stable ponte or double knit) to a 50% (a jersey) to 200% and up (activewear). Some activewear can stretch 2 to 3 times it's original relaxed state.

Hopefully, this will help you not only choose the correct fabric, but will help you in the assembly of your fabric.

July's August's Feature Resource

Well, sometimes I outsmart myself, and a very kind subscriber pointed out that there was no link to the Core Patterns, so I'm going to keep this up for another month, with the special price, for those of you who tried to click something that wasn't there!

-

🤦♀️

Core Patterns are a great way to get to simplifying not only your sewing but also the selection process that you go through in selecting projects.

I personally keep a list of visual ideas on Pinterest (which is so perfect for this) so that when I'm perusing the net, I simply add photos or pictures to my Pinterest page, and make a little note like "Neckline," "Lapel," "Scarf," and on like that to draw my attention to that part that I like. Sometimes it's color or color combinations, sometimes it's a simple way that a collar rolls. Sometimes it's the whole dang thing.

Then when I get those, "I need a new red top," or "I don't have a good red top to go with all the red bottoms I have," or any other harebrained idea, I can simply check out my Pinterest page of ideas and boom I'm off and running.

Then there's finding the pattern, or even worse having to draft the whole thing up from scratch. But lately I've been turning more and more to my core patterns and with a little manipulation of those patterns, I have a pattern that fits, that's flattering, that's comfy and that is fairly time-efficient to make up.

These are all from my core knit pattern.

Now how do you pick out a core pattern? What makes a good core pattern? What are some ideas for variations? How do you avoid pitfalls in fabric selections for blocks or different sections on a core pattern?

And this resource also includes another bonus - how to better choose fabrics for your patterns and how to better purchase online fabrics that will work with your projects.

As usual this resource is 15% for the month of August - click here to see more..

PS - I do a lot of posting on Facebook as SewingArtistry - like my page to see more goodies!

To view this email in browser or to see past emails click here. (This works now and is a lot of fun to check out!)

We respect your email privacy

|

|

|

|